Although I’ve never been the biggest fan of football managers and sports games in general, I remember playing Sensible World of Soccer endlessly back in the ‘90s. I was utterly blown away by the fast arcade gameplay layered over a comprehensive but, at the same time, incredibly data-rich game. To me it was, and still is, my favourite blend of action and management in a football game. I still have it on disk with the most recent rosters to play occasionally. I have always wondered how you did all that team and player research from all those obscure worldwide leagues in such a scope back in the pre-internet era.

Ah, good question! We worked with a guy called Mike Hammond. Mike writes something called the European Football Yearbook – or did at the time. Now, he writes for UEFA – their annual book. His job is to research players across Europe. That’s what he does for a living; he is paid as a book writer. I can’t remember how we met Mike, but it was a perfect fit, because he could just get extra money by using his data in a different way than he already had. So we would just say to him, ‘Okay, on top of your data about the name and the team and the shirt number, we will want playing stats for these seven different skills: passing, hitting, tackling, speed, etcetera.’ In the end what happened was that Mike had the whole of Europe covered already. He just had to convert it to our format. He worked with a guy called Serge van Hoof. Serge did all the Non-European stuff and Mike was managing him, so for us it was really very easy. We told him the format the data needed to be delivered in and he did.

For me, all the SWOS ever was an electronic Subbuteo you didn’t need your dad to play against

We’re using a very similar system with the Social Soccer – the game we are working on now with a guy called Dave White. He was the guy who’s been keeping the database of Sensible Soccer alive all these years. There is a system of tracking players: someone needs to track the movement of players in the real world and people being signed in the real football world. Once you’ve done that and you add players and you kill them off when they retire, you keep the database up and running. That’s pretty much how it worked back then. I guess it was amazing to people that we’d done that. It was pre-internet and it’s probably important to point out that Sensible Software’s success was all in the pre-internet era.

What were the main advantages of such a time in regards to Sensible Soccer and SWOS?

It was less mass media; which means that the users were slightly more gravitated towards enjoying computers, enjoying innovation, and weren’t so much social sheep. We tended to do quirky, weird stuff, like we’d throw Wizkid or Wizball into the mix along with straight stuff like Sensible Soccer or Cannon Fodder. Everything was accepted for us, which was really great in those times. Also the graphical demands of games were less. I’m not the world’s greatest graphical artist. I think I was capable of creating iconic art that people remember and that functioned – did its job well and looked clear and nice enough – which was good enough in those days. For every game we’ve spoken about so far, I did 100 percent of the art – apart from the intro sequence for Mega-lo-Mania, which was done by a guy called Joe Walker.

Then the industry changed and demanded more artistically, more like television. But before that time, the SWOS reached the peak, it was one of the top-ever home computer games. So, it was it was enormously satisfying for me – who as a young boy used to play Subbuteo and wait for my dad to come home from work to ask him to play again. For me, all the SWOS ever was an electronic Subbuteo you didn’t need your dad to play against. You play against a computer or you could play against your friends when they were around. I’m proud that we’re the first game to have Black players and players with blond hair and all the different countries. That with all the attention to detail, the love, the accuracy – which I’d learnt from 3D Tennis, by the way. To be able to do all that and for people to respond was great. Also, to be able to get people like yourself. Roughly one-third of Sensible Soccer players are people who don’t like football, but they love the game, because the game worked. But the football fans also loved it because it really acknowledged football. It’s interesting how we managed to achieve that.

Cannon Fodder is my favourite all-time classic. Its soundtrack is burnt deep into my cortex. It is still one of the most ridiculous and perfectly playable games today. I only recently learnt that the recruitment music is a cover of your 1984 tune ‘Narcissus,’ which is a terrible earworm. What is the relevance of this tune to the game theme?

I think we’d already done ‘War Has Never Been So Much Fun’ as the title tune. Which was just a fancy little loop, because it needed to fit in the memory we had with real singing. I don’t know whether you’ve heard this story before, but we stumbled upon the idea of putting the soldier names up for all the guys who died. That was because we started to name the soldiers, then we showed the soldiers ranking up to get better medals for the winners, and as an afterthought we put the names of the guys who died. Then we went, ‘oh shit look how many people really died!’. It’s not real war – you forget about the casualties – and so we made this thing so that you couldn’t click away from the list. You are forced to look at the guys you’d sacrificed to win your level, and to level up the couple of guys you cared about. That’s the key message which comes from the game in the end – which again didn’t enter the game till one year into development. We never deliberately did it. We stumbled upon it and then like any good game developer, we caught the good idea, because it is obvious.

But then we needed the music to go with it. We had some music to celebrate the guys levelling up, but then we cut it back to just have a little bit of music [hums the tune] which happens when you end the level and that’s the celebration. Then we we needed a sad tune to try and push forward this idea of people dying. We basically milked the dead people; we could see it worked. We threw poppies on the screen and we put the graves in afterwards.

I had this tune I wrote when I was 18, from 1984, when I split up with a girlfriend. I was sad about her. She went off with my best friend which was great [chuckles] and it was the first time I’d felt any kind of love for someone. So, I wrote this song with words and I was round at Richard’s house one day. We were working on quite a lot of projects together, because we had Cannon Fodder and Wizkid going, which had lot of music in it. We had Sensible Soccer going at the same time, Mega-lo-Mania kinda finished when Cannon Fodder started. So I was at his place a lot and I think I just took the tune around to play to him. I said, ‘what do you think of this?’ and we decided to try it out.

It is actually one of the tunes me and Chris played live when we were wearing rubber masks and I wore a dressing gown and Chris wore a dress. I was playing this sad song and Chris ran on in the middle of the stage with his lead guitar five times too loud, playing a bleeding solo over it to kill it – cause he felt like it, which was fun. But then his lead fell out, cause he ran too far across the stage, and it went totally silent. I could continue with my mournful song, which is good for me. So yeah, we just dropped the words out and replaced them with the melody you know and it worked. What was interesting is that Virgin called onto it and actually backed us to do a decent recording of the song in the studio that a friend of mine owned in Clapham. I’m actually recording a version of it right now with Andrew Barnabas. We’re doing a new version as we speak for a new album of games music that’s going to be coming out sometime soon.

Although I have never played Wizball’s bizarre sequel called Wizkid, developed in 1992, I managed to watch some gameplay videos of it on YouTube recently. Since then I wondered, what substances were used in order to produce such a crazy looking and sounding game?

This was the last game me and Chris Yates made together as just a pair of us. We were using no drugs, we were young kids back then [chuckles]. We were just messing around, you know. This is like free-form jazz as a game. We threw whatever ideas we wanted together and we could make anything work. Chris was brilliant at taking a rigid structure and then putting all the crazy ideas around it. It somehow held together. That was a great expression of us working together. For anyone who has not played Wizkid, it’s a really out-there game. It’s a game I’m proud of and I love the fact it sits between Sensible Soccer, Cannon Fodder and Mega-lo-Mania. These four games sum up what Sensible Software was: Mega-lo-Mania is a kind of out-there game – and also the first game to have a tech tree – Wizkid is just crazy, Sensible Soccer is a straightforward, well-researched football game, and Cannon Fodder is a well-executed combat game.

With that line of stellar titles, you entered, albeit rather briefly, into the golden era of Sensible Software…

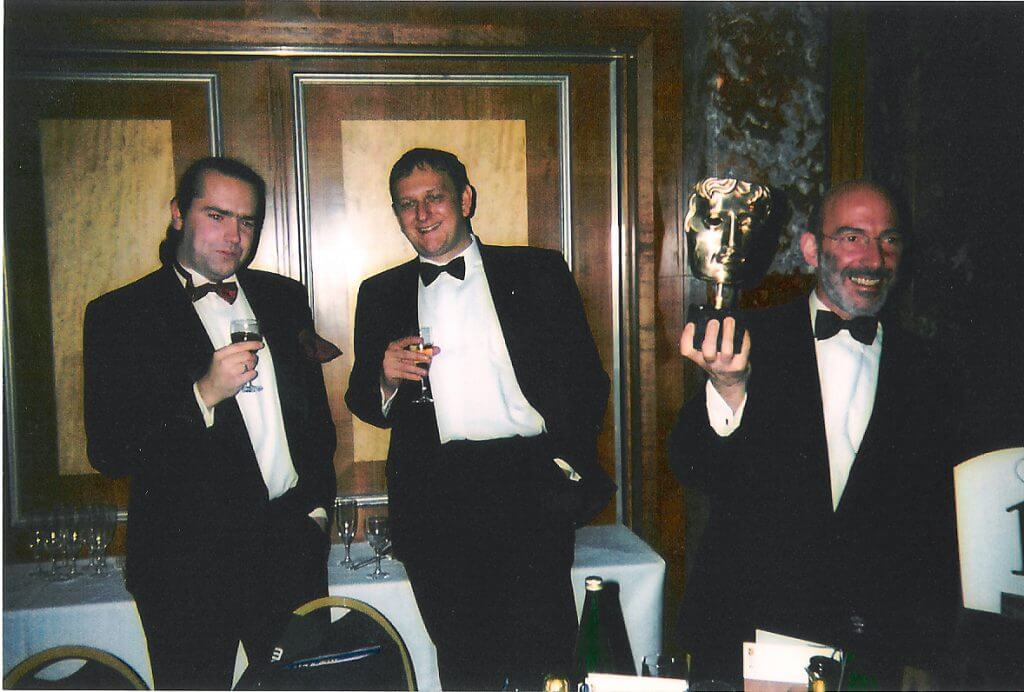

We were on a roll. Most of what we were doing was turning to gold. We made a lot of money in the mid-‘90s years. We had our best ever deal with Renegade; we had a 50 percent royalty rate, which is pretty much unheard of in those days. We also did Cannon Fodder 2, SWOS and a secret football game for Sega under a different name, which was basically the Sensible Soccer engine repurposed. We signed Sensible Golf, which was not a good game, with Virgin. It was not a good game purely because we were doing too much at once. We were doing about three or four games at once and we didn’t want to up the manpower too much. Also, we did Sensible Golf on the Cannon Fodder engine, which was a bad idea. We kind of bit off more than we could chew, but we did it. We’d been seven years working in the industry without a lot of money and suddenly we were the top guys – probably in the world or certainly in Europe – in the home computer era of the time, and we just cashed in. But in doing that we kind of stretched our resources a bit and it showed a little bit in Cannon Fodder 2, which wasn’t as good as Cannon Fodder 1. It showed a lot more in Sensible Golf. They both still did well and got to a number one; they’re not failures.

The obligatory question: What eventually killed Sensible Software?

Ironically, what killed us was exactly what you mentioned earlier, business-wise. We were in a situation in 1995 where we had three games on the table we wanted to make. One was a Sensible Soccer follow up in 3D. One was a game called Sex’n’ Drugs’n’ Rock ‘n’ Roll. It’s an adventure game about a rock band that me and Chris had been designing since before we set up Sensible Software, within about a year of meeting each other when we were 16 or 17. It was a joke game about people with seven different drug habits trying to keep it all going and run a band and stuff. Also a game called Have a Nice Day.

At this stage, we didn’t make that much money from Wizkid, although it was a lot of fun working with Ocean and Gary Bracy again on it. But we had a lot of money coming in from Renegade for Sensible Soccer and a lot of money coming in from Virgin for Cannon Fodder, and from Sensible Golf as well. What we really wanted to do was to just keep our relationship to those two companies going. But both of them said they wanted to buy out all of our products. So we were forced into a situation where we had to put all of our eggs in one basket with either Renegade or Virgin with a three-game deal. To a certain extent, it helped us, because you can kind of play companies off against each other in that situation. We got offered an amazing deal – even now for any indie studio this would be an amazing deal – and we were getting this in 1995, so 23 years ago. So it was Sensible Soccer (3D) and Sex’n’ Drugs’n’ Rock ‘n’ Roll for PC and Have a Nice Day for Playstation – just one format for each.

many people asked me, why did you stop doing Amiga games? It’s because no one would buy them from us.

It was a three-million-pound advance deal on a 50 percent royalty. Now, to anyone who doesn’t know that business too well, maybe they don’t understand how good that is. 50 percent royalty is pretty amazing for a developer, and the advances were like four times more than we’d ever made before – for three games. So what really killed us, was that we certainly got too greedy, too ambitious and we didn’t at all understand how much extra work 3D was compared to 2D. In 1995, we’d not touched 3D yet really. We were earning a lot of royalties from SS and CF and we thought everything we touch would turn to gold. We totally underestimated the extra matter of programming and art needed for 3D. Then we totally underestimated the fact that we needed middle management to manage the extra people. We didn’t have any of those things in place and we made a lot of very bad hiring errors actually, mostly with programming in that learning 3D period. We were already one or two years behind other companies who had gone to 3D earlier, whilst we were milking and enjoying the end of the 16-bit era.

Other people have moved on to other stuff. Because, as I said, we were probably the most successful developer in Europe at that time on and those machines, but other people who weren’t that successful moved on to the new stuff. So when we suddenly looked up in ‘95 and went, okay, we’ve got to do 3D because no one wants to sign up 2D games anymore, many people asked me, why did you stop doing Amiga games? It’s because no one would buy them from us. We were a developer, not a publisher; we needed to sell to somebody. So we had to move. We were forced to link to 3D and when we got there, we were hopelessly behind. But we had money from our royalties and we had a great deal. We had a three-million-pound deal which was totally unheard of. When you consider that nine years earlier on Parallax we got a 5,000 pound deal, and now we were getting a million per game, it’s quite a royalty jump from 15 to 50 percent. We were hiring people, but the thing was we had to hire quickly. We had also been really lucky previously. Chris Chapman was amazing – he did MLM and SS as the lead programmer. Dave Korn was great. Jools, who did CF and SG, was great. Martin [Galway] hadn’t worked as a lead programmer, but he was a musician anyway.

But then we just unluckily hired about two or three pretty bad 3D programmers in a row. We didn’t have the experience of vetting and we didn’t have an HR department. Chris always expected people to be good and if they weren’t, he just fixed their work when they weren’t in the office [chuckles]. Suddenly, he got to a point when he couldn’t do that. He was learning 3D himself, not C64 3D, but for PlayStation and struggling with that himself. I think he’d admitted to that. It wasn’t as easy as he thought it would be and he didn’t have the time needed to back up the other programmers. Whereas in the years when we’d done CF and SS, Chris had done all the background work to support the other programmers. He did the different conversions of the game like the Nintendo version for example, he did the version for Sega and he did Wizkid and he was always in the background doing stuff. He couldn’t give the support in the same way for the 3D machines either. We basically lost the ability to effectively do everything needed to make top quality games.