Jops, real name Jon Hare, barely requires an introduction. The veteran developer, musician, consultant, businessman and educator has been a household name of the British and European games industry for over thirty years. Jon has held the scene’s spotlight since his Sensible Software heyday. His rich industry experience has not only been sought by other developers, but also a number of universities. His current project, Sociable Soccer, seeks to introduce his classic magical formula to the new generation of players – and bring a great deal of refreshed nostalgia to the others. But let’s rewind. Our story begins with a college dropout who wanted to be the next big rock star…

Hello Jon! Let us start with the most important question. What’s your favourite football team?

Hello! My favourite football team is Norwich City. That’s easy. I’m a fan.

Great, so now all the pub quiz masters can check this one out! Anyway, what’s the backstory of your famous nickname, Jops or Jovial Jops?

It actually comes from my sister. I’ve got a younger sister, just one sibling, and we used to make stupid names up for each other because you do when you are kids. And she was calling me Joppy at this time. It was when I started to know Chris Yates, who I set Sensible Software up with. Chris was a close mate my of mine. We were in school together, we went to the same maths class. I guess I first met Chris when I was 15 and my sister had been 11 or something, and she was calling me Joppy. So Chris, to take the piss out of me, started calling me Jops, and it kind of stayed with me. Then when it came to making the credits for our first ever Sensible Software game, Parallax on the Commodore 64, Chris took it to the next level by adding me in the credits as Jovial Jops, which he tried to balance up by calling himself Cuddly Krix, both names steeped with irony. He managed to shake off the nickname, but I didn’t. My wife still calls me Jops to this day and a lot of my older friends in the games industry still call me that too. It’s kind of stayed with me my whole life. I mean, in order to be slightly more professional, I tend to put my name as Jon these days [laughing]. But there was a time when everyone was calling me Jops. It’s fun to have a nickname.

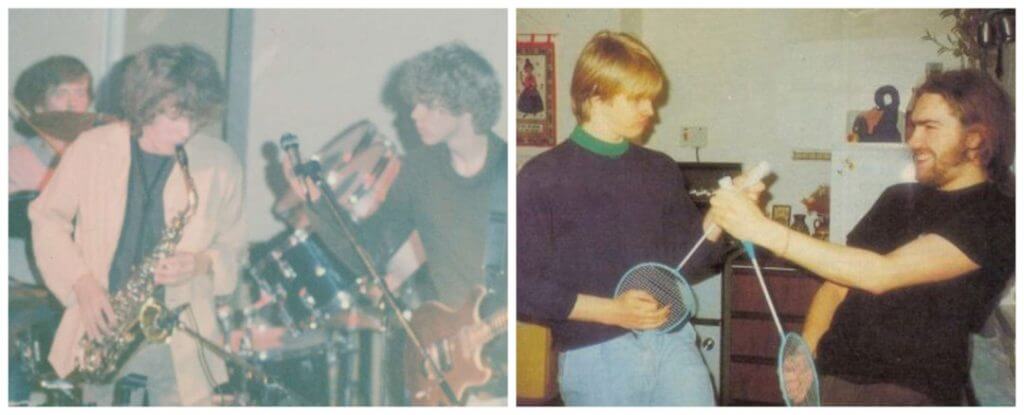

Before turning to Sensible Software and the games, I’d like to hear more about your musical background. It’s well-known that you and Chris Yates were bandmates in several music projects. Could you briefly sum up that era?

We we were in the last year of high school, so 15 to 16 years old, when we became friends. We met going to a Rush gig – the Canadian band. We met on the train back with a couple of school friends of each of ours and we pretty quickly became friends. I lived maybe a half-hour bus ride away from the school, whereas Chris lived a five minute walk. Chris lived with his dad who wasn’t always home, so we had a pretty free rein of the house. I found it quite attractive when I became friends with Chris; to go to his house rather than standing around waiting for the bus in the rain. And yeah, we started to make music together. Chris had a guitar and I had an old acoustic guitar at home that I had had since I was a child. We started to try and write songs, I suppose you could call it. Chris was a good guitarist for his age and I was terrible, but I could sing a bit and make words up. So it naturally gravitated to me to write the words with Chris playing the guitar; writing the music together, we originally called ourselves ‘Deuce’. Then I learnt how to play the bass because we needed the bass player. A young lad at school said he was a drummer, but actually had only saucepans really.

We did one gig, we both wore rubber masks and I wore a dressing gown

We did our first gig under the name of ‘Zeus’ very near where Chris lived and we both went to school, in Chelmsford, Essex, in a scout hut in a park. I think it was quite cold, it must have been in January or February. I remember that this guy, when we got him a drum kit to play, he really couldn’t play the drums at all. It was to the extent that we did a cover of ‘We Will Rock You’ by Queen – which, as you probably know, has got a very simple drum beat – and he couldn’t do it. We weren’t very good, you know, but we thought we were Rush. We were three 16-year-old kids who were learning and rubbish. But we persisted; we got rid of that drummer, changed our name to ‘Hamsterfish’ and me and Chris carried on writing music. A friend of mine – a few years older – lent us a four-track Tascam [recorder], and we became recording partners. Chris developed a talent technically. He always had it anyway.Mixing, producing, messing around with effect pedals, getting a screwdriver out and pulling things to bits; that’s Chris’ world. I would sit there and write lyrics and we’d do chords together; it was just a very natural partnership. Then we started to play some gigs locally with another local drummer, now under the name of ‘Dark Globe’. One time, barely over 18 now, we had a gig in a local village hall where about 100 people came to see us, which is quite good when you’re a young band. We’d make our own tapes, and we had a guy who said he’d be our manager. I remember someone stole all the money from door that night. I don’t know how many gigs we did like that in that band, maybe about 20 or a bit less.

Then we stopped doing that band after a while. We got a local following, we kept on experimenting and recorded three albums, we were always changing what we were doing. We would alienate the audience sometimes by doing some crazy stuff. We did one gig, we both wore rubber masks and I wore a dressing gown. Chris was in some kind of dress I think and we went on to play as a two piece. So straight after our most successful gig with a hundred people, we threw a total curve ball, ditched the new, better, drummer and briefly transformed ourselves into ‘The Amazing Technicolour Dream Globe’. It was mostly rock music or rock-influenced music. I guess I tended to write a lot of ballad slower acoustic rock stuff as well. So there’s a mixture of that and straight rock music. Then, a couple of years later, we met these bass and drum players. Jack Grigor and Ron Bennett from Chemical Alice, who used to be support band for Marillion. Do you know Marillion, the British band? In the ‘80s, they were a successful prog-rock band – a relatively new ’80s band. We managed to pick up their old drum and bass player by fluke, so we now had a good rhythm section. I went back to playing with rhythm guitar and Chris was playing lead and keyboard. I was doing the singing and lyrics and we were writing the music between us. That was fun. This new band was called ‘Touchstone’ andat was probably the best band we had at that time. I think Sensible Software started out somewhere in between the Amazing Technicolour Dream Globe and Touchstone.

How did you come up with the idea to start making games?

Okay, so in terms of the games, the first game we ever made was a war game. Chris’ dad left a wallpaper table in the room and then he went abroad. We drew a grid out on that table with a ruler and pencil, then a map of different terrain and rivers and forests, and all these pieces. Kinda think about it like a really early board game prototype of Cannon Fodder. We did that when we were about 16 to 17 – this is three or four years before Sensible Software. Also, I remember even when we were at school – we would have been 16 – Chris was getting these weird computers. I mean, it was even before we got a Spectrum. In this computer, we put naughty words to the nursery rhyme ‘Sing a Song of Sixpence.’ And we made a funny little game called ‘Escape from Sainsbury’s’. This is before SensiSoft – we were in a creative partnership, basically, that’s the way to think about us. So, it was very natural for us when Chris got a Spectrum. It was just an extension of all the other stuff we were doing. It was like another little machine and certain things to do in between writing the music. But, at that time, neither of us had jobs. We both dropped out of college before we’d finished our courses. He’d done computer science and I’d done some arts, drama courses and theatre design – a qualification which is about the art around theatre, lighting, stage sets and stuff like that.

Chris managed to get a Spectrum from various catalogues. Basically, when you got the Spectrum, you could send it back within the same month for free. He did that three times in three different catalogues; enough times to teach himself to program. Then he made a demo and actually got a job from a local company. It was very inventive of him. He was doing some work for them and they needed him to do some art, but he couldn’t do it. I was at his house one day for music and I said I’ll have a go at that art. So, I drew a dragon and a wizard and stuff that was needed for the game he was doing, and he put it in the game. The company liked it and then they offered me a job as well. That was how we started. We spent about nine months to a year working in that company. Then we realised they were actually taking 85 percent of the money and we were doing 100 percent of the work on those games. We decided to leave and set up our own company, which the UK government made easy at the time, so we did it.

Graphically, you could be very experimental in those days. Baddy was a baddy, he was just a blob of pixels in the sky

Why Sensible Software?

I can’t remember why we called it Sensible Software, but I do remember one thing. I remember once we came up with that name, I liked it because ‘sensible’ and ‘software’ have both got eight letters. So, the initial Sensible Software logo has got a big ‘S’ at the start and the big ‘E’ at the end, then all of the other letters are written in between. I think we were stoned talking shite and came up with this idea. I don’t know if you remember a band called The Damned, but they had a guitarist called Captain Sensible, who actually contacted us years later. He was known by then and it was around that time, so they might have had some small influence on our thinking, but I don’t really remember. I was just playing around with what was on a page at the time.

Your first ZX Spectrum game already hinted towards the tongue-in-cheek presentation style that would become your signature. The simple pseudo-3D arcade shooter, Twister: Mother of Charlotte (1986), had to have its name changed due to a slight controversy. Could you tell me a bit about that?

This was a game we did when we weren’t yet Sensible Software. We were working as freelancers for this company called LT Software, which was relatively local to us in Essex. But System 3 were kicking around then and LT Software were getting a lot of their work from Mark Cale. He had this idea for a game called Twister: Mother of Harlots, which basically means mother of whores. He literally said to us, “I want it to be like Tron and I want a woman with big tits flying around as the main boss,” and that was pretty much it. So she was called Mother of Harlots and she was flying around. Initially she was naked. But then Mark changed his mind and so we cleaned it up by changing her name to Mother of Charlotte and putting a bra on her. But it still had these weird caterpillars with bongs flying around and stuff in the sky, etcetera. Graphically, you could be very experimental in those days. Baddy was a baddy, he was just a blob of pixels in the sky. We made a pretty good Tron game at the time. Yeah, that was the first game.

Did you consciously decide that the games you were going to make would always have this extra layer of wry humour?

It was totally natural with me and Chris working together. Chris had a pretty vicious sense of humour. We actually had a very similar sense of humour and we didn’t consciously put the stuff in there. It was just part of the way we worked together. Actually, in the UK, it’s nothing special to be like this – especially at that time, before we had to think about political correctness and getting sued legally, which are the two things that shut people up now. There was humour in everything – any radio programme in the morning, anything on the television or in the newspaper – jokes were just part of what we do. Maybe, in retrospect, we became a company that could carry that kind of British humour to a European audience, which is quite nice really. It was not our intention, but that’s what ended up happening.