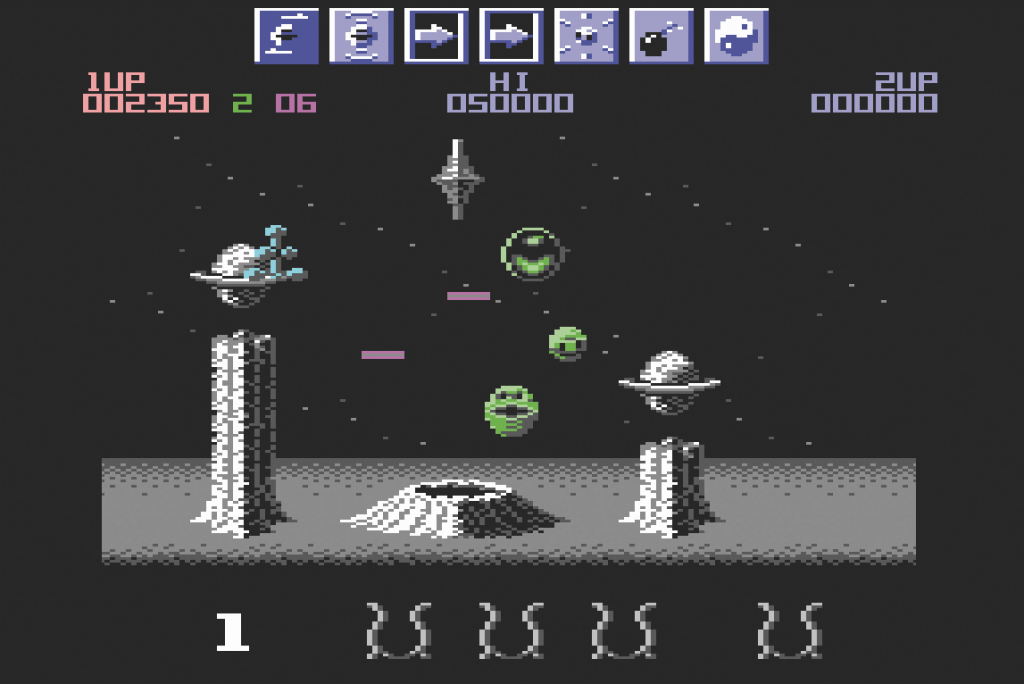

Parallax, which derives its name from the cool scrolling feature of the game, also includes other interesting features such as drugging scientists on a rescue mission. Then there’s the very trippy chiptune music by 8-bit composer legend Martin Galway. How did you get him involved?

It happened like this. So, Parallax was our first game as Sensible Software. It was the first time we had to do any business and try to sell a game. We were extremely lucky. We set Sensible Software up in March of 1986 and, after two or three months, we had a demo of Parallax. We contacted Ocean who were the top publishers in the country at the time and they invited us up to Manchester to show them the game. It was great, we were very lucky to get a deal that first day. We got a cheque for a thousand pounds and a contract for 5,000 pounds – albeit it was a terrible contract. It got signed up that day. I think we were around 20 at that stage. I was 20, Chris was 19 and Martin was an 18-year-old guy just working in a small room in the office. He was one of the junior people at Ocean and happened to be doing their sounds. I remember we went back there – not the first time, but the second or third time – and Martin said, ‘Oh, I’ve made some kind of tune-up for the game, what do you think?.’ He sat me and Chris down and it blew us away. That Parallax music still pushes the hairs up on the back of my neck to this day. It was a brilliant work by Martin and of course he did Wizball for us as well.

you work with programmers of varying quality, and they have a colossal impact on the quality of the work you do as a designer

And Martin eventually became a full member of Sensible, correct?

When we got a little bit further down the line in the company. I think it was just around about the time before we made Microprose Soccer [1988] that Martin joined us as a partner. He was the only other partner we ever had. I guess these days you’d call it a shareholder, but we didn’t think about it in those days. He joined for a year and a half. It wasn’t smooth sailing because there wasn’t enough work for a musician to work full time. So Martin wanted to push himself to do more programming because he was quite a technical guy and obviously did some level of programming for his music. He started working on a game with me called Touchstone which was signed provisionally to Origin Systems in the States – the guys who made Ultima. It was quite a big, ambitious, Ultima-style adventure. As a designer without having someone to control me, I just went crazy, and unfortunately for Martin, he was struggling to keep up with it. Then Origin asked us to move from the Commodore 64 to the PC. That kind of move was the last straw and Martin couldn’t handle it. We ended up having not enough work for Martin to do music-wise. After that year and a half, Martin moved to America to join Origin as their sound guy. So it kind of worked out for the best in the end. It was an experiment for me and Chris.

In various stages and different companies – not just Sensible Software – you work with programmers of varying quality, and they have a colossal impact on the quality of the work you do as a designer. That was maybe my first experience of someone who was not up to doing all the programming they’re expected to do. Which is no slight on Martin at all – he is one of the greatest computer musicians who ever lived – but I think he learnt a bit about himself then as well.

So how exactly did you split the work back then?

At that time, I did all the art for all of the Sensible Software games. Chris did all the programming and we shared the design – certainly on the Commodore 64 games. Although I ended up taking on more of the design than him on the Amiga games when we got there.

In 1987, SensiSoft released its first megahit, Wizball. What do you think were the crucial ingredients of its success and how did you even come up with the idea?

Wizball was the third game Chris and I had created together – after Twister, which we basically made and designed ourselves and Parallax. We’d learnt the ropes of how to create a game. I think that, with Sensible, the background of having written music and three or four albums together prior to making games was highly beneficial for us as a creative team. We learnt how to make things together, how to bounce off of each other, how to polish stuff, etcetera. So when we came to Wizball, it was based – like nearly all the games in the ‘80s – on arcade machines. We didn’t have a lot of home computer stuff to play. There was really only the Atari VCS when we were growing up, and obviously the few games on the Spectrum and C64 like the ones we were making. Wizball was very much influenced by Defender and we’d been playing Dropzone, which is a great Defender clone by Archer Maclean.

Then I guess this idea came from my study of lighting when I was doing theatre design. I was quite interested in the way that you could construct colours with the computer – the RGB stuff. I liked the idea that we could colour the landscape in somehow. We weren’t sure how initially and then we came upon the idea of paint droplets as an enemy. We’d start the landscapes black & white and then go to colour. After that, we just added the idea that they’d go somewhere to collect paint droplets, and then they mixed the paint somehow. That’s where we added the laboratory. Then we go to the laboratory and it’s kind of boring. ‘Okay, what can we add? Oh, let’s have a satellite which goes ‘meow, meow’ like a cat when you fire it. Let’s make a cat come out of that ball’. Actually, Chris had a cat called Nifta who was always around the house when we were working. We were literally in the spare bedroom of his house at this time. He had Flintstones wallpaper on the wall of the office, it was made for a six-year-old boy, it was lovely.

So we made this cat come out of the little ball and then we decided that a wizard would come out of the big ball. Okay, so now we’ve got this character, a wizard and his cat, and that’s really where the name Wizball came from. It wasn’t called Wizball for quite a while, whilst we were doing other stuff. That’s how games kind of work, they kind of find themselves. Then we did the colouring of the levels. Then we added multiple exits from different levels. The way you can complete levels in a different order, which we retained in the Wizkid [1992], that’s an area of its originality. Pretty much that’s the game and there’s only eight levels. It was just a good scrolling shooter with a bit of imagination behind it.

Probably the most unusual title you have ever released is the Shoot’Em-Up Construction Kit, which shipped in the same year as Wizball. I can’t think of many popular game editors from the pre-internet era, which in my book makes SEUCK pretty unique. Was it a rather accidental creation or something that was carefully planned out as one of the first public game-making programmes?

When we’d done Wizball, we kind of learnt how to construct games by holding onto something and building pieces around. It’s pretty much like making a piece of music; construct layers, allow yourself to jazz out sometimes, but make sure there’s a firm beat behind it. When we got to SEUCK, the intention was we wanted to make games more quickly to make more money, because we didn’t make much money out of Parallax, Wizball or Twister. We were basically earning enough money to live and then go on to the next one. We didn’t get any royalties from Ocean, who – let’s say that maybe their accounts department was a little creative – always ended up with a zero at the bottom of the royalty statements. We’d also done a couple of budget games by then: Galaxy Birds and Oh No with BT Software’s Firebird.

Chris made an editor for me to make games fast, so we could basically sell them. I started making a game called Slap and Tickle, then other ones called Outlaw, Celebrity Squares and Transputer Man. I made four. Celebrity Squares is terrible. But we wanted to show different types of scrolling shooters. Slap and Tickle was a space shooter – just vertically scrolling, quite straightforward. Outlaw was more about walking around and shooting people in a Western environment. But the problem was the games weren’t that good, they were nowhere near as good as Parallax and Wizball. I said to Chris, “The editor you’ve made is brilliant, that’s really a good editor.” So we talked about it and decided that we’d flip it around and actually sell the editor rather than the games, because we could see that there wasn’t value in the games. My work just became to show off the editor Chris had made. We worked mostly around tightening up the editor and the usability of it, and then we sold the whole thing to Palace [Software]. It was the first time we’d sell something to someone other than Ocean. Actually, that’s not true because all the budget games were for BT. That kind of gave us an extra source of income and SEUCK was our first number one game, ironically. So yeah that was fun. Yeah, I’m not sure if that was the most original thing we did, but it was different to all the games we did, because it’s an editor rather than a game.

1988 was a year that might be considered seminal for you, for one particular reason other than getting Martin Galway onboard. You released your first football game, this time for Microprose. It would serve as a precursor to the game that elevated you to superstar notoriety. It was packed with all the nifty and ridiculous features the later game was famous for: impossibly long tackles, crazy spin animations – but also easy controls – fast gameplay and the revered ‘banana kick,’ allowing for incredible ball swerves. I’d like to hear the story of how you came up with such a rich variety of original features for an 8-bit computer football game.

Well, it is pretty much like with all the Sensible games: they were based on a solid foundation. I think we were lucky to learn this early. In Parallax, you’re flying around in a spaceship. Once we got that bit going, we could do the bit about drugging scientists – and actually we wanted that to be a much bigger game because the basis worked. You know, fly a spaceship around, create physical rules, create levels, and you’ve got the basis of the gameplay. The same with Wizball. It’s a side shooter. Then when you come to Microprose Soccer, it’s the same; it’s a solid football game. In all three cases, they are influenced heavily by old arcade machines.

Now, I’m working on Sociable Soccer. It is literally 30 years afterwards and I’m still doing it

In Microprose Soccer’s case, it was influenced by a tabletop arcade game called Tehkan World Cup. Probably the biggest football game of 1987 to ‘88 I’m guessing, and it had a trackball. So you had a trackball to move the players and two buttons to pass and shoot. It really hurt your knuckles to play it, but it was a good game. And if you look at it, Microprose Soccer pretty much looks similar to it. Same kind of camera angle, same kind of size players. I guess the initial scope of the game was to convert that kind of playability and graphics to the C64. So we got the basic football going and then these slide tackles and so on, but the banana shot was interesting.

I read a few years ago that Tehkan [World Cup] appeared to have a small swerve in the ball sometimes, and it was a bug [chuckles]. We picked up on this and added this intentional ability to swerve the ball – albeit crazily unnaturally in Microprose Soccer. C64 was our format by then – like any computer programmer allowed to work on the same format a few times before the technology changes. Chris had become kind of a C64 master. Graphically, we decided to double-layer the sprites. We had the fat four colours per block sprites, with brick-style pixels to define the basic colour of the players. Then we overlaid on top of that a two colour sprite with smaller more defined black pixels as an outline on top of the multicoloured ones to get a different graphical definition than had been seen in C64 games to date. It gave the players more of a cartoon look, which at the time was an improvement. The gameplay, to me, is quite slow now. It’s much slower than the current game we’re working on and a lot slower than Sensible Soccer. But for then it was great and CVG called it ‘The best sports game of all time on any computer’ at the time, so we did really well.

Once we got that solid basis of a football game, we added some teams. I think, at the time, we added international teams only for the World Cup, which was basically what Tehkan World Cup had. Then we added a really cool ability to rewind and see goals, and this tape effect on the rewind, which was nice. It went black and white to do the rewind part. Flashing off a replay, no one had done that before. And then we tried to sell it under the name of Sensible Soccer.

Which leads us to a novel American publisher involvement by Microprose…

We went to a few companies, and in the end, Microprose offered us the best money. It was almost double what we’d ever had before for a game – on the condition we changed the name to Microprose Soccer. We did because we needed the money. Because they’re American, they wanted us to add this indoor soccer, because indoors six-a-side was the only soccer game played in the States at the time. So we put that in and we put in all the teams in the American league – Reno and other places. Have you ever been to Reno?

Nope.

It’s like a poor man’s Vegas. Anyway, so we put all those teams in there and got the game out. Martin [Galway] did the music for it and I wrote a stupid tune to promote it. It was the first game we really got behind and tried to push a bit with an image of ourselves in the game shows. We made some T-shirts. It was our first toe in the water trying to promote anything ourselves. I’m a football lover anyway, so it was great to make a decent football game. It was a stepping stone in learning how to make sports games. Now, I’m working on Sociable Soccer. It is literally 30 years afterwards and I’m still doing it, so I’ve got quite a lot of experience. My problem now is that most of the people I work with don’t have a lot of the same experience as me on sports games, so often you’re teaching people stuff you learnt a lifetime ago.