One year later – after Flashback’s massive success – a subsidiary of Delphine, Adeline Software International, was established. During their short life span, they became famous for their Little Big Adventure games. What is interesting to point out is that the team mostly consisted of ex-Infogrames members. Namely, people who had previously worked on the Alone in the Dark franchise. How did they get involved with you?

We were two different entities; they stayed in Lyon and we worked from Paris. Paul de Senneville approached them when he learned that Fredéric [Raynal] was quite upset that he could not get his credits for Alone in the Dark 2. All the credits went to Infogrames, so he wanted to do something else. He was given the chance to form a second team, Adeline, to create something new. We used to meet from time to time, but we never worked on any projects together. We were two teams financed by Delphine.

Having the big Electronic Arts come to us and tell us we were good and that they wanted us to do something for them made me feel pretty proud. We could not really resist it

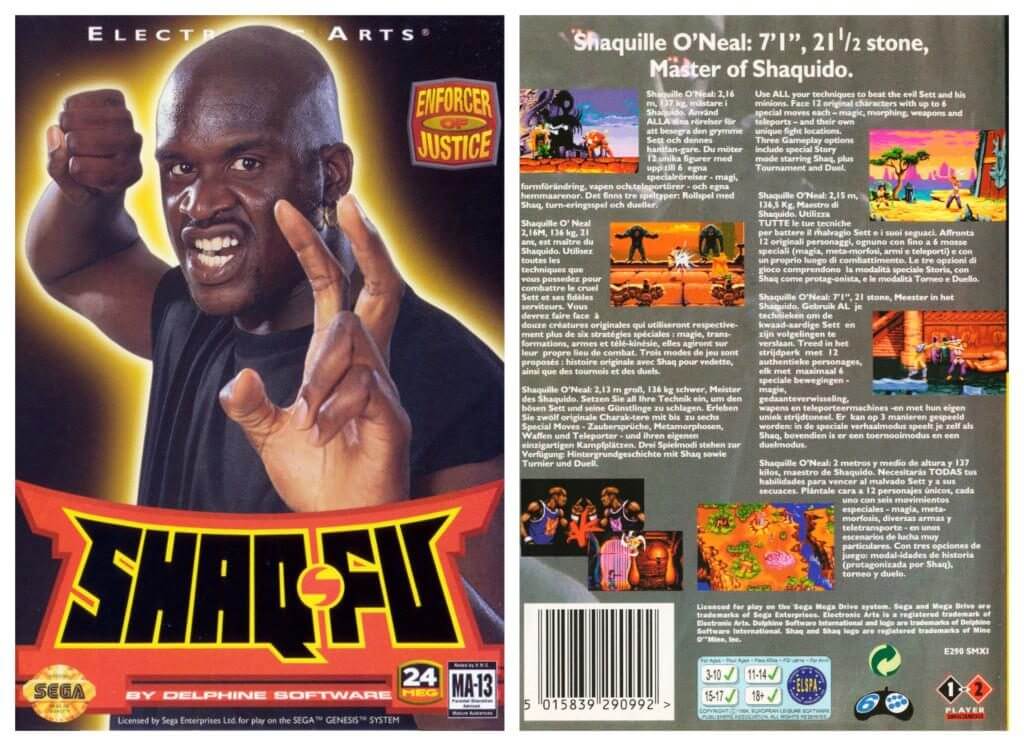

Not very long after that, in 1994, a controversy cast a shadow on your unstoppable period of hit-making. At the time, you had again been experimenting with something completely different. Shaq-Fu was a Street Fighter-style game, published by Ocean and Electronic Arts respectively, with famous NBA celebrity Shaquill O’Neil as its main protagonist. Do you personally consider the game a failure?

I think that there was quite a lot of hope for this game. We were approached by EA, who wanted us to work on a game with Shaquill O’Neil. They put forward the idea of a fighting game. They also wanted us to use rotoscoping as they were fans of Flashback. This was very interesting for us as a small French company. Having the big Electronic Arts come to us and tell us we were good and that they wanted us to do something for them made me feel pretty proud [laughs]. We could not really resist it, so Paul said, ‘Okay, you’ve got to create this game’ and we started on it. But it was absolutely not anything we’d done before; we had to reinvent things as we were not specialists in fighting games.

For the first time, we were very pushed by marketing and EA would not have any delays. It was very difficult as the company had to grow very quickly. There were only ten of us working on Flashback and we grew up to 40 people on the Shaq-Fu project. That was very hard to manage as we were used to a small team where people knew each other and knew how to work together. It was very difficult to get something consistent out of it in the short period of time we had for the development [one year].

So, from my point of view, it was not really a failure, because it got us working on something interesting and different. But there were external forces fighting with the game [laughs]. We wanted to have something subtler with animations and combat. We had a lot of animation frames, but they wanted to have something more like Street Fighter and really pushed us in that direction. That’s why the game is not consistent; it goes in one direction and then in another, which explains why it didn’t really succeed. Also, the idea of having Shaq O’Neil in a fighting game was quite strange.

Yeah, it was difficult project despite the high budget. But, even with a big team, you cannot create a polished game within such a short period of time.

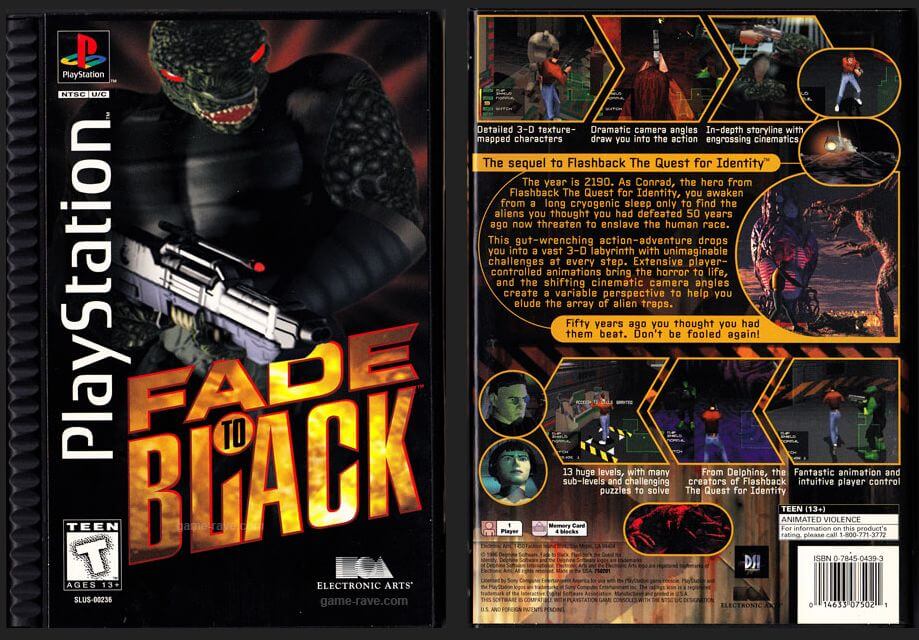

Similarly, Flashback’s sequel, Fade to Black (1995), also received a rather mixed reception. Critics complained about its high difficulty and its low-poly 3D graphics mired with a problematic third-person camera. Do you think it was perhaps too early to switch into full 3D?

No, I don’t think so. I think that all things have a consequence. When EA approached us to work on Shaq-Fu, the sequel for Flashback was already in production. So we had to separate into two teams, one working on each game. At the time, 3D looked quite interesting and I really wanted to go in that direction. But I was very involved in Shaq-Fu as that was the big project for us. So the Fade to Black team worked on their own. Frankly, they did quite a good job, because they created a brand-new 3D engine. It was on PC and we didn’t have any 3D graphics cards at the time – everything had to be written in software – so they could only choose the technology that was available [laughs]. One of their technical inspirations was Doom and Wolfenstein, which is not even proper 3D as it is based on a ray-casting system.

I joined the team after finishing Shaq-Fu. What I missed in that engine, due to the technical limitations of the time, was the lack of platforms; everything had to be on one level. Delphine had already invested one year into its development, with eight to ten people working on it, so it was not possible to restart the project. Thus I had to forget about the idea of having climbing walls, etc. The concept was very different and we tried to experiment, but we faced a lot of technical issues. We had to invent a lot of things in the process.

What about the accursed camera that people were complaining about?

It was the first time we had used a virtual camera and we just didn’t know what to do with it, how to handle that. For example, one problem we encountered with this early third-person camera was where to place it – when the player went back to the wall, and so on. There were just too many technical issues and it was very difficult to put it all together at that time. So yeah, Fade to Black was quite a good experiment [laughs]. But we really had to invent everything from scratch and lost a lot of time researching and developing, then throwing things away and restarting, etc.

The hard times of the early adopters!

Oh yeah, definitely! [laughs]