1990 was the year that marked a new era for Dynamix. The studio was bought by Sierra On-Line and lost, albeit temporarily, one of its founding fathers Jeff Tunnell, who started his own studio. It was also the year that spawned the legendary Red Baron. What are your memories of that turbulent 12 months?

It was a good time. We made a deal with Sierra – with Ken Williams – and the main point of sale with the company was that we remained autonomous – creatively autonomous. Because that was what kept us excited and enthusiastic about making games. He totally agreed; he was an entrepreneur himself and he understood. He didn’t want just to acquire us and then shove his ideas down our throat. He could see a lot of acquisitions that worked down that ladder, while the others failed. So I would credit him with a lot of wisdom in the way he managed us. We were certainly

willing to work hard when we did the sale to Sierra, cause we still loved what we were doing. Funny thing is that he did an interview with a local paper and said, “Oh yeah, these guys are 30 people now and in a year they’re gonna have 120 or something.” And we are like, “What? This guy is crazy!” But he was right, because he was willing to write the check. So we just started hiring people and we started to do projects for Sierra, and difference was that the budget’s got way bigger. Sierra understood that what you wanted was a hit and you should invest more; you should have a better game and you are just gonna make much more money that way.

‘Oh no!’ We thought we were going to somewhere where nobody was around and suddenly everyone’s here

Then Jeff branched off to do his own thing, but he was still essentially part of Dynamix. He was sort of a sub-label of the whole thing. It was JTP [Jeff Tunnell Productions], but I think it started under the Sierra label. Basically, he just a got a little studio here in Eugene of 10 to 12 people. But it was basically the same thing, he just wasn’t in the same building. I don’t really know how it worked out financially, but anyway, it wasn’t like a big break-up. He just wanted to do his own things for a while.

For me, I wanted to do another flight game and I wanted to do historical. My original idea was to do something called The Great Warplanes – WW1,WW2, Korea, modern – it was gonna be everything.

That concept reminds of a game by Microprose called Dogfight, where you could fly triplanes against jets.

Ah, okay! Yeah, EA ended up doing something like that later too [perhaps Chuck Yeager’s Air Combat].

So, that was kind of my idea and then I got a letter from Ken Williams. I didn’t really have much contact with him, so it was like, ‘Oh, jeez!’ It was a little bit scary – ‘what’s this about?’ He wrote a very formal letter, but basically he just – he was very kind – he said, “You know, we found at Sierra that the best way to do this is to do sequels. Instead of doing them all at once, it would be better if you just do one thing and then the next thing.” That sounded right to me and I actually liked it; I could just focus on one era. So that’s how we ended up doing Red Baron to start. And we were playing a game called Fokker Triplane on Mac that was very fun, but it was very arcade-like. It didn’t have any depth, didn’t have any history, but still the core gameplay was fun. Ah, the core gameplay is fun and that’s the thing: you always want the core game loop to be fun and then you can add all the layers on top of it. That was kind of the inspiration for Red Baron.

Red Baron was released at the same time as its rival Knights of the Sky by Microprose. I only properly played the latter back on my Amiga 500. However, Red Baron 3D has become my personal all-time favorite historical flight sim. How come two such similar big titles were released head on in the same year? Was one a direct response to the other or was it a coincidence, or something entirely different?

I think it was a coincidence and I think it was because Larry Holland had done Their Finest Hour, Battlehawks 1942 and The Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe. So, someone had already done WW2 and I think everybody was like, ‘this idea of doing historical flight simulations is a neat idea, but we wanna avoid WW2.’ That’s kinda what my thinking was, so I think that maybe everyone else had similar thinking. Because it wasn’t just us and Microprose; there were about three others at the same time. There was Blue Max, Wings and there was even another one – I can’t remember now. It was crazy and we got scared when we found out that everybody was suddenly doing this. We thought, ‘Oh no!’ We thought we were going to somewhere where nobody was around and suddenly everyone’s here. So that was like, ‘Oh jeez, now we are in trouble.’

After Red Baron’s massive critical success, Dynamix achieved the formal status of an accomplished flight sim developer and followed up with its Aces series. Again, shoulder to shoulder with their rivals from Microprose. What was your relationship with the guys from Microprose in general? How well did you know each other?

They were just competitors and I always, of course, was envious of their success, because they were successful earlier than we were. Going way back, I don’t remember what was their first big game. Maybe F-117 Stealth – that was huge for them – and there were some other ones even before that. They were the top company in the simulation area for sure; nobody was close to them. We were surprised how quickly we overtook them. I am not saying we passed them, but we certainly got on par with them and I think our products started being better than theirs. I think it was really our 3D expertise that was one of the reasons we had a competitive advantage over them. I think we had better technology at that time than anybody for 3D. There was a moment when we had the best stuff and I think later that changed. Maybe around ’93 to ’94, other companies started coming along. They were rivals, but I didn’t dislike them. I knew that Sid Meier was such an amazing developer. He stopped working on their sims at some point. I have even met Bill Steele at some conference and you can tell, he was a really competitive person. He would just make a little jabs at your product [laughing].

We were terrified of Knights of the Sky and when it came out we were really happy, because once we played it, we realized that we had nothing to worry about. It just wasn’t there. It wasn’t the real experience, not how I would have expected. I didn’t think it was as good as the stuff they had done before. They went for this cutesy retro – oh, things were really cute back then in WW1 – and they were flying these cute little planes and they all had scarves. It wasn’t like that; it was a terrible time for the pilots. For the pilots, it was a terrible war. It started off when they were all excited, like, ‘Oh this is great, this is chivalrous, we are all above the fray.’ But, by the end, especially for the German pilots, it was horrible. They were doing two flights a day and they would go up to 10 to 20,000 feet. It’s freezing up there and the oxygen’s bad, their brain is just dead, their friends are getting shot down left and right. It wasn’t a cute, fun time. It was sort of romantic and beautiful – like the planes and everything, I mean, there was a nice side to it – but there was a dark side too, obviously, and I felt you need to kinda capture that a little bit.

It is fun to build. There is a lot of things you can do in life; building is one of the funnest things you can do

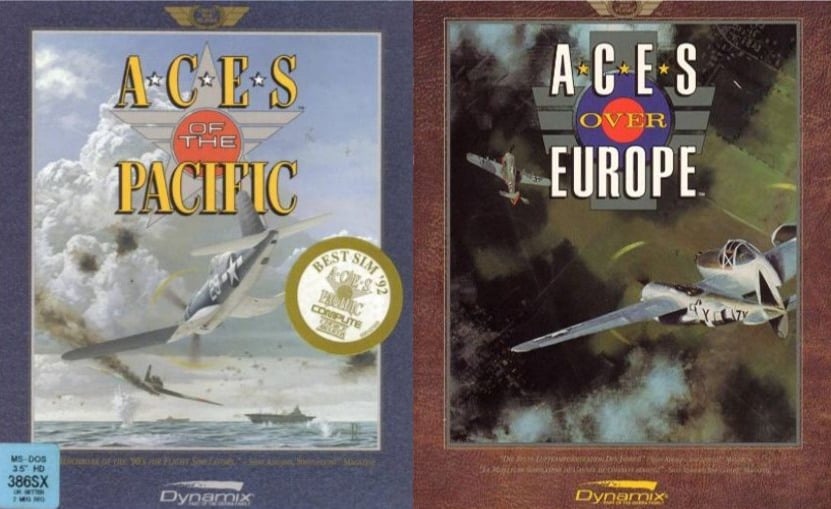

Aces of the Pacific and Aces over Europe were the last games you developed for Dynamix. Which of these is your favorite aerial warfare game, and why?

It’s still WW1 Red Baron. I think that was the best product we did. Technically, the other ones were a little better. We made some improvements in Aces of the Pacific and Aces over Europe – some graphic improvements. And the scope of Aces of the Pacific was way larger than Red Baron – it was huge and had carrier landings. You can fly for five services, not just for three, and there were a lot more airplanes. So the scope was a lot bigger, but Red Baron was really focused and tight. I also I think that the dogfights were more fun, because the planes were slower, so that meant they were also closer together. I think that part was a little better. But WW2 was still pretty good in terms of the quality of the experience for the player. I think the modern era is really not at all the same; the dogfights are too big and there is too much electronics. I like WW2; I would have liked to have done more WW2 combat games, something really focused, especially, with better technology.

In 1994, you suddenly departed from game development and left Dynamix for good. How can a seasoned developer suddenly drop out at the peak of his creativity? What were the driving forces behind this hiatus, and why did it take so long for you to return to making games?

I was burned out and I had really done nothing since high school but make games. Right when I graduated from high school, I started working full-time on Stellar 7. That was in 1980 and from ’80 till ’93 or ’94, I was just working many hours making games. Of course, back then we would do overtime like crazy – it’s not healthy [laughing]. There was one week, I remember, on Arcticfox when I worked 105 hours and I was sleeping at the office. Even on Aces of the Pacific, the team was working 70 hours a week for a while – it was crazy. You don’t have a life anymore; you don’t have a personal life. So, there is that, and I had never really done anything else. I thought I should go back and do my degree. I was making a lot of money, but life shouldn’t be about money. So I just kind of burned out. If I was smarter, if I was wiser and older, I would find a way to keep making games; I would have just changed the way I did it. I would have scaled back to normal hours and just done things I enjoyed, and I would probably stick around longer. Cause it’s kind of an honor to be able to lead a team and make cool games, and it’s fun. It’s fun to collaborate; that’s why I came back to doing it again. And I probably would have tried some other kinds of games.

Ever since Stellar 7, I wanted to do a game where you can get out of the tank and you can run around as a person. I had always wanted to that, and later on, that became a new genre. I would have probably ended up doing something like that. Something like Tribes, cause that was after I left.

So what did you do when you were not making games – or rather, what made you come back? Did you get bored of life outside games?

Yeah, I just realized that working is important – you should work – and it’s fun to make games, it’s fun to work with people. There’s lots of parts to life. Before, I was only doing one part of life, which was working, but the solution isn’t to not work. I think I should have just added balance. I also realized that I missed working and that I want to make things. It is fun to build. There is a lot of things you can do in life; building is one of the funnest things you can do.