Two of your early publishers were EA and Activision, which are nowadays the behemoths of the industry. How do you remember the experience of making games for them back in the ’80s?

They were very different to what they are today. They were new, they were embryonic; compared to what they are today, they were tiny. At the time, they seemed huge, cause they were the biggest. When we went to Electronic Arts – that was the first company we worked with – and when we pitched to them, we were really intimidated. We went to their office – they had these fancy offices in Silicon Valley – and the thing is, later on, Dynamix was bigger than what EA was at the time we first pitched to them. They had this big board room, and I remember when we did the pitch and we were sitting in the board room, there was a mic hanging down from the ceiling. We were the only ones in there and we were like, ‘Oh! Are they listening in on us to find out our secrets? We gotta be careful!’ [laughing] You could just see that there was a lot of money in it, so it was kinda scary.

a ‘captive developer’ – that’s the phrase we used back then – because you would never kick into your royalties stream

What was it like to actually work with them? Joe Ybarra was a pretty creative guy; he was the producer there and he played a lot of games, so he was always pushing for more ideas. EA back then were more product-driven. At some point, they became almost entirely market-driven and moved towards relying on the license. Back then, when they were more product-driven, they had this whole artist mentality; they wanted to push the artists more like a record label. So they certainly could get the game out to a much bigger level than we could. Arctifox sold, across all different computers, about 150,000 units – which sounds like nothing today, but back then, that was a lot. They were good at doing that stuff. But the business relationship was tipped in their favor, because they were sharp and they were savvy and we didn’t know what we were doing. The way the deals worked out were such that very few artists would kick in their royalty stream. They were giving an advance for development and then you’ve got royalties on the back end and you just couldn’t really build your company very effectively.

But that wasn’t a problem particular to Electronic Arts. I think that was, in general, a problem we were aware of that all developers were experiencing – that you are a ‘captive developer’ – that’s the phrase we used back then – because you would never kick into your royalties stream, or a very little. So you are constantly having to sign new projects, and you are using the project you’ve just signed for salaries. It’s robbing Peter to pay Paul, so to speak. You are sort of on a gerbil treadmill; you are just running in the wheel and you are not going anywhere; you are never getting ahead financially. But I think what we didn’t realize – and they didn’t realize – was that, in an intangible way, you are getting ahead. Because what you are doing is building a team, you are building expertise, you are creating and you are building a technology base, so you have sort of intangible assets. Eventually, that saved us. We got really good at making games. Publishers didn’t – they had studios that did – but they didn’t know how to make games.

Dynamix is known for its versatility throughout its 17 years of creative history. I believe I am not exaggerating too much by saying that almost anything it touched was turned to gamer’s gold. You are known as the main creative honcho behind its 3D simulation and action games production. However, you are also credited in games that don’t quite fall into that category. The C64 exclusive side-scrolling action adventure, Project Firestart, is considered by some as the grandfather of modern horror survivals. What’s the backstory of its development? Who came up with the idea?

That was a game for Electronic Arts – and again, remember when I said they wanted to do movie games like Karateka? Eventually that came back around, so we got green lit to do Project Firestart. I was the original designer and director on it and, about half way through the project, I was busy with other things, so I turned it to Jeff and some other people. For me, the inspiration was Alien, which is kinda obvious. I love that movie and I love Ridley Scott, and it’s a sci-fi horror, and we wanted to make something like that. It was strange, cause I had to study something that was way outside of my field. My area was simulations, 3D and math. So I got fascinated with movies, and I read several books on how to create suspense – that is way outside of the math guy’s background.

How do you create suspense? What’s the crux of that? And it’s literally suspend; you have something that’s about to happen and then you cut away, so you leave the audience in suspense. We tried to build these kinds of things into the game when something is happening, then, oh, you cut away. There is this terrible thing about to happen then the user tries to solve it. It was fun, but I think it was really hard to scare people back then, because hardware, basically the hardware. I think that games like Doom did a much better job – I think Doom was really creepy. Firestart was still a neat game, but [laughing] there was a scene in Project Firestart where you’re gonna shoot the monster, and it has to go to the floppy disk to load the monster, and it takes like thirty seconds [laughing]. They obviously know something’s happening. Oh! The disk is spinning out, what’s gonna happen? It kinda ruins the whole mood.

Amiga sort of died when everybody realized that it just wasn’t gonna make enough money for people

There was some other fun stuff on Project that I really liked. On the technical side, there was some really cool sprite stuff we did on the C64 to be able to pull off some of the scenes. There was a scene where you run through a tube in space and it has multiple views of scrolling and things like that, and it has some really fancy sprite stuff. Basically, we were able to get more sprites on the screen than C64 has. I think that’s amazing.

When I watched a gameplay video today – because I have never played it myself – I was struck by how neat the game still looks. Immediately, I thought, ‘Wow, that’s a game I would have liked to play on Amiga.’

Yeah, I agree, that would have been a great Amiga game. It would have solved a lot of technical problems and the audio part is where we would have focused. The reason is because we stopped working with EA. I think if we kept on with them we would probably have done ports to the Amiga. It would have been perfect, of course. Although, EA at that point had just really lost interest in Amiga. When they first approached us, they wanted us on Amiga; everything was about the Amiga. Trip Hawkins bet 100 percent on Amiga and then we got a letter from Trip, when we were working really hard on Amiga, starting off with, “Hey, and this is for everyone, if you know 6502, start coding.” 6502 is the CPU of C64 and Apple II. They are the old, crap – relatively crap – computers. Basically, he was just telling everyone, ‘We are done on Amiga. We need to move back to these computers, cause this is what it’s all about.’ And he was right, that’s where all the money was. Amiga sort of died when everybody realized that it just wasn’t gonna make enough money for people.

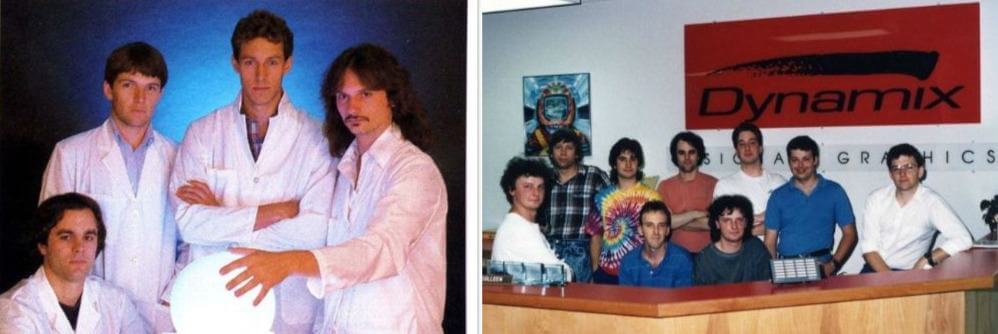

The year 1989 sees Dynamix as a creative powerhouse. Besides Project Firestart, the studio released seven more titles – something unheard of in our era. How big was the studio back then?

I think we were 30 people. Yeah, 25 to 35, something like that. I think that was a great year and that’s why Sierra wanted to partner with us; because of that, because they saw what we did. We had been talking with Ken Williams at Sierra and he didn’t believe that we would be able to ship all those titles that year. We were talking to him a year before they shipped. We said, “Oh, we’re gonna do all this,” and he is like, ‘Oh, you’ll never do that, nobody can do that!’ But that’s what I said. We got really good at making games and it’s almost like a cheesy metaphor, but you know the book Dune with the Fremen? They live out in a desert and there is no water and they are really strong because of that. I think that is kinda like we were. We were living without water, where the water is money. We were living out in a desert with no money, and you just really learn and get good at what are you doing. So I think being a ‘captive developer’ for so long and surviving, you just get really good at that and you build good technologies and things like that. I think that’s why – because it was hard for us – that’s why I think we got good. We had to ship those titles, we had to! [laughing] The money came attached to the milestones, so if you don’t get it out, you don’t get paid and everybody gets fired.

That year brought us, among others, your first proper flight sim, A-10: Tank Killer, and the first Mechwarrior video game from the Battletech universe. Both games were seminal, each in its own league. Whilst the Mechwarrior series would carry on under Activision’s banner, it also inspired Dynamix’s own mech series Earthsiege. A-10 had kick-started a golden age of flight sims. Let’s start with few words about the first Mechwarrior. What was your role in its development?

I was the original designer and director on Mechwarrior. We had done a deal with Activision to do five games for them, and two games they would affiliate to publish for us. I was actually a director on four games at that time – it was too much [laughing]. So I was on A-10, David Wolfe – which was our other movie game – Mechwarrior and another game called V-22 Osprey that never got shipped. They all were gonna be through Activision, but two of them we were gonna self-publish with their help and they had the Mechwarrior license.

That was a big budget for the time; it was the biggest budget we had ever had on any game and they had the license from FASA. My role was doing initial design and directing it for a little while. It was actually one of the easiest designs I ever did, because all I had to do is just take the books – you know, the Mechwarrior books – and I would just go and cross things out and say, “No, we are not going to do this,” circle something, “Yes, we are doing this. Here is how we do this.” It was really easy [laughing], because it was all laid out and I knew what you could do on the computer. I understood computers really well, so I knew how we could simulate stuff. I actually felt guilty about it and at one point I talked to the lead programmer and I said, “Man, I don’t even feel like I did anything,” and he said, “No, no, it was good because that was all I needed to program it.” It was almost like the value was in saying what you are not gonna do. So, it was really just a lot of, “We are not gonna do this,” and “This, we are gonna do this.” In a way, it was the easiest work I have ever done. It probably just took three days or something, just to go through and figure it out.

It felt like a real simulation, but we would still do a lot of things in the service of fun and making sure the gameplay was interesting at all times

That was it for my involvement and I turned over – oh! What happened was that we hired a producer from Activision, Terry Ishida, and for some reason – I don’t know what happened – he wanted to come and work with Dynamix, so we hired him. He took over Mechwarrior, cause he was on the other side of the table before, and I said, “Yeah sure go ahead!” And then he also took V-22 Osprey. That was great. I was happy he did that, cause I didn’t really have much time anyway. We were loaded, so it was great to have him.

A-10 was instrumental in discovering the right balance between realism and accessible gameplay; an essence that was later poured into all future flight-sim projects that Dynamix developed. Was this your concept?

Yeah, I’ll be immodest, but yes. I started making arcade 3D games like Stellar 7 and Arcticfox and then a little bit of sci-fi thrown in it. I didn’t start making simulations straight up. We had done a game for Electronic Arts called Abrams Battle Tank and that was sort of halfway in between arcade game and simulation. I played some games that were really straight simulations and they are impressive in their own way, but to me it’s still gotta be fun [laughing]. What’s the point? I mean, a straight simulation is, I guess, interesting to some people, but I still wanted to do mass-market games that were fun. Games like M1A1 Abrams tank simulation are probably never gonna be mass-market exactly. Whoa! I shouldn’t say that, look at World of Tanks now; they’ve figured it out.

So, I have really come from a place of doing arcade games and really having an emphasis on it has to be fun! In some ways, I think that Abrams was a failure, cause it was right in the middle and it didn’t really fit very well in either space. I think that A-10: Tank Killer started to work. I still it has some flaws, problems with it, but it started working. It felt like a real simulation, but we would still do a lot of things in the service of fun and making sure the gameplay was interesting at all times. So yeah, I would agree to that. I think you have figured out the philosophy pretty well for those games. It was about making something feel realistic and authentic. I used to call it psychological realism – not documentary realism – as you are simulating the experience of a pilot.